Nice work by

William Amos, M.A., LL.B/B.C.L. Director/Directeur Ecojustice Environmental Law Clinic at the University of Ottawa Leblanc Residence 35 Copernicus St., Rm 110, Ottawa ON K1N 6N5 Tel: 613.562.5800 ext. 3378 Fax: 613.562.5319 wamos@ecojustice.ca

Conclusion

Although a handful of proposed amendments to the NWPA in Bill C-45 may enhance protection of navigation and navigable waters, the overall deregulatory impact will be to weaken Canadians’ public right of navigation. In essence, the federal government is doing its utmost to “get out of the business” of protecting navigable waterways across the country, except for three oceans, 97 lakes, and portions of 62 rivers. The majority of Canada’s waterways will not be subject to statutory navigation protections, leaving citizens clinging to the leaky lifeboat of common law in the fast-moving currents of economic growth.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

Legal backgrounder Bill C-45 and the Navigable Waters Protection Act (RSC 1985, C N-22)

Overview

For 140 years, the protection of navigation rights and the waters that enable it have been core to the federal role in environmental governance across Canada. The Navigable Waters Protection Act (NWPA) is one of Canada’s oldest federal environmental laws, enacted by Parliament in 1882. The NWPA built upon pre-existing common law navigation rights and the federal government’s exclusive jurisdiction over navigation and shipping pursuant to section 91(10) of the Constitution. Since that time, the NWPA has protected the rights of Canadians to navigate Canada’s waterways without interference from logging operations, bridges, pipelines, dams, and other forms of industrial development.

The interrelationship between navigation and the environment is such that the protection of the former consistently promotes the health of the latter. Consequently, the NWPA has consistently served as a federal tool to achieve environmental protection. Indeed, Transport Canada’s own documents clearly recognize what the federal government now denies: That one of the NWPA’s goals is to ensure the “protection of the environment.”1

The Supreme Court of Canada, in Friends of the Oldman River Society v. Canada (Minister of Transport), examined the constitutional validity of federal environmental assessment guidelines and cited the NWPA as a valid federal statute that legislated with respect to the environment. The court stated:

“…it defies reason to assert that Parliament is constitutionally barred from weighing the broad environmental repercussions, including socioeconomic concerns, when legislating with respect to decisions of the nature. The same can be said for…navigation and shipping. [Sections 21 and 22] of the Navigable Waters Protection Act are aimed directly at biophysical environmental concerns that affect navigation…the [NWPA] has a more expansive environmental dimension, given the common law context in which it was enacted.”2

1 Government of Canada, Navigation Services, online: Marine Services On-Line

2 [1992] 1 S.C.R. 3 at paras. 88-89.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

As discussed in greater detail below, the deregulation of federal navigable waters law first occurred in 2009. Those amendments to the NWPA — like the ones proposed by Bill C-45 — were passed as part of an omnibus budget bill tabled by the then-minority government. The changes significantly weakened environmental protection of Canada’s waterways, most notably by reducing the number/types of projects subject to NWPA approvals that “triggered” a federal environmental assessment process. Their enactment amounted to an end run around democratic process: they were not subject to a detailed clause-by-clause analysis by Parliamentary Standing Committees, and were not subject to any significant debate prior to a confidence vote which tied the hands of opposition parties.

The most recent amendments to the NWPA, tabled on October 18, 2102 in Bill C-45, would further weaken navigational and environmental protection of Canada’s waterways. These amendments would change the statute’s name to the Navigation Protection Act (NPA), a change that reflects the government’s desire to completely separate navigation from the environmental component that enables it. In other words, the law will no longer protect navigable waters — it will only protect navigation.

Although regulation for the sake of regulation is not desirable, the proposed amendments go to the opposite extreme: the NPA would exclude 99.7 per cent of Canada’s lakes3 and more than 99.9 per cent of Canada’s rivers4 from federal oversight. For the few navigable waters that remain regulated under the NPA, the protection offered by the law will be significantly weakened.

While Bill C-45 contains some changes that may enhance the protection of Canada’s navigable waters, the overall effect of the proposed amendments is a dangerous deregulation of Canada’s waterways that will make it difficult, if not impossible, for Canadians to enforce their long-standing navigation rights. The amendments go far beyond what is necessary to reduce “red tape” for beleaguered cottage-goers, farmers and municipalities that propose small projects (e.g. docks, footbridges, etc.). Under the proposed NPA, proponents of industrial development and large infrastructure projects (e.g. Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline) will be given free rein to disrupt and impact Canadian waterways without regard to either navigation or environmental rights.

Why does Canada need strong federal protection of navigable waters?

There are several reasons why we need a strong federal law to protect navigable waters:

The Canadian nation was built, in part, on the public right to navigation. Although transportation and commerce are no longer entirely dependent on navigation, many businesses depend on unimpeded waterways for their economic well-being. A strong federal law ensures that tourism, recreational fishing and angling,

3 The federal government lists the number of known lakes in Canada at 31,752. Natural Resources Canada, The Atlas of Canada: Lakes, online: Natural Resources Canada

4 It is estimated that Canada contains over 2.25 million rivers, 62 of which are protected under the NPA.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

and other outdoors-related businesses do not suffer economic harm from development that interferes with navigation. As well as protecting businesses with a direct interest in the waterways, a strong federal law also protects businesses that are supported by recreational paddlers and fishers, such as outfitters, outdoor gear retailers, restaurants and hotels. A strong federal law that protects all of Canada’s waterways ensures that businesses located in small communities can continue to create long-term jobs and generate economic returns for those communities.

Protecting navigable waterways also protects the economic and health benefits provided by the water itself. A strong federal benefits Canadians by ensuring that development does not negatively affect water supplies, fish and fisheries, and natural water purification and filtration services. Besides providing obvious health benefits to Canadians, these indirect effects may also help communities economically by reducing their infrastructure needs.

A strong federal law is important to the fulfillment of Canada’s international obligations under the Boundary Waters Treaty. Some of Canada’s obligations under that Treaty are dealt with in the International Boundary Waters Treaty Act,5 but many are not. For example, Article III of the Boundary Waters Treaty requires Canada to seek approval of the International Joint Commission before permitting interference with the natural flow or level of boundary waters. However, under the NPA, Canada would not regulate a number of boundary waters, jeopardizing the government’s ability to comply with the Boundary Waters Treaty, resulting in international tensions and exposing Canadian taxpayers to liability for damages claims.

Since the government holds Canada’s waters in trust for the benefit of Canadians, it has a duty to protect the public right of all Canadians to navigate waterways in a fair and transparent manner. This duty falls exclusively to the federal government, which is granted sole authority over navigation and shipping under section 91(10) of the Constitution. Provincial governments have no authority to regulate navigation on any Canadian waters, so there is no question of intergovernmental overlap and duplication.

Although the common law may be used to protect navigational rights above and beyond the terms of the NWPA, reliance on the common law embraces a reactive, rather than proactive approach to protecting navigable waters. In other words, the common law will generally only fix the harm after it has occurred. By proposing to turn back the clock and rely on common law precedent to protect most navigable waters, Bill C-45 improperly shifts the federal government’s responsibility to enforce the law onto citizens. Citizens will be forced to pay out of their own pockets to bring lawsuits against the federal government or project proponents, resulting in delays and uncertainties as the judicial system grinds along. The common law is also not well-equipped to deal with a situation in which a series of small works, none of which substantially interfere with navigation on their own, have cumulative and substantial impacts on navigation.

5 International Boundary Waters Treaty Act, RSC 1985, c I-17.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

History of the Navigable Waters Protection Act

The NWPA was enacted in 1882. Although the primary purpose of the law was to protect the public right of navigation, the law was instrumental in achieving the protection of Canada’s rivers from obstruction and pollution related to industrial logging activities.6

Although the law remained largely unchanged until 2009, the enactment of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA) enhanced the level of environmental protection provided by the NWPA. Under CEAA, the issuance of an approval under the NWPA triggered the federal environmental assessment process.

In 2009, the government passed amendments that significantly weakened the NWPA’s protections for navigation and the environment. The amendments introduced a tiered classification system for waterways and significantly narrowed the classes of waterways protected under the NWPA. In addition, the amendments granted the government unfettered discretion to further exempt certain classes of works and waterways from the NWPA’s approval process. Pursuant to the 2009 amendments, exempted waterways were not subject to the approval process, meaning that they no longer triggered a federal environmental assessment. The amendments also reduced transparency and accountability by eliminating the need for public notification and consultation on all projects that the government determined would not substantially interfere with navigation.

In July of 2012, the federal government passed the Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act7, which re-wrote and scaled back the federal environmental assessment process. As a result, NWPA approvals no longer trigger any federal environmental assessment ever, further weakening a previously interconnected federal regime of navigational and environmental protections.

How does the NWPA work?

The term ‘navigable water’ is not exhaustively defined in the NWPA, where Section 2 provides that a navigable water “includes a canal and any other body of water created or altered as a result of the construction of any work.” The definition of navigable water at common law has evolved on a case-by-case basis, based on the factual circumstances of each case. Over a century ago, the Privy Council established the “floating canoe” test for navigability, resulting in a low threshold to assert the public right to navigation.8 In 2011, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice concluded that the common law of navigability “requires that the waterway be navigable” and “must be capable in its natural state of being traversed by large or small craft of some sort.”9

For its part, Transport Canada offers a similarly broad definition, reflecting many of the principles established at common law:

6 Benidickson, Jamie. The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage, UBC Press, 2007.

7 Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act, S.C. 2012, c. 19.

8 Quebec (Attorney General) v. Fraser (1906), 37 S.C.R. 577 (S.C.C.); affirmed [1911] A.C. 489 (P.C.)

9 Simpson v. Ontario (Minister of Natural Resources), 2011 ONSC 1168.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

“In general, navigable waters include all bodies of water that are capable of being navigated by any type of floating vessel for transportation, recreation or commerce. *Note: Frequency of navigation may not be a factor in determining a navigable waterway. If it has the potential to be navigated, it will be determined ‘navigable’.” 10

Prior to the 2009 amendments, the NWPA provided significant protection to both navigation and the environment. The NWPA prohibited the construction of any work in, on, over, under, across, or through a navigable water without approval from the Minister of Transport. Projects that would not, in the Minister’s opinion, interfere substantially with navigation did not require an approval. However, in recognition of the fact that, by their very nature, bridges, booms, dams and causeways always substantially interfered with navigation, the NWPA provided that these projects always required an approval, regardless of the Minister’s opinion.

In order to obtain an approval, the proponent had to submit a project description and plans to the Minister. The NWPA required that the proponent give the public one month’s notice of the proposal through advertisements in the Canada Gazette and two newspapers. Since this requirement applied before the potential triggering of a federal environmental assessment, public participation opportunities were guaranteed even if the Minister decided that the project would not substantially interfere with navigation. Where the project would substantially interfere with navigation, a federal environmental assessment was required before the Minister could issue an approval under the NWPA.

Failure to obtain a required approval was an offence subject to a maximum fine of $5,000.

The NWPA provided the Minister with powers to remove obstructions, such as sunken vessels, from navigable waters. The NWPA also prohibited the dumping (in navigable waters or waters flowing into navigable waters) of debris or any material liable to interfere with navigation. The NWPA further prohibited the dumping, in navigable waters less than 20 fathoms (1 fathom is approximately 1.8 metres) deep, of materials liable to sink to the bottom. Cabinet had the power to exempt specific waterways from these prohibitions, if it was not contrary to the public interest to do so, and the Minister had the power to designate certain navigable waters as dumping places. Contravention of these provisions attracted a maximum fine of $5,000.

The NWPA empowered the Minister to make interim orders where “immediate action is required to deal with a significant risk, direct or indirect, to safety or security.” These orders were subject to strict transparency requirements, in that they:

Expired after 14 days unless approved by Cabinet;

Had to be published in the Canada Gazette within 23 days after being made; and

10 Transport Canada, Frequently Asked Questions, online: Transport Canada

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

Had to be tabled in both Houses of Parliament within 15 days after being made.

NWPA as amended in 2009

In 2009, the federal government passed amendments that significantly weakened the NWPA’s protections for navigation and the environment. While these amendments did not affect the dumping prohibitions and the obstruction powers, they opened the door to reducing the number of waterways protected by the NWPA through the introduction of “minor works” and “minor waters” orders.11

Almost immediately upon passage of these amendments, then-Transport Minister, John Baird, issued an order exempting certain classes of works (e.g. small culverts or dams) and navigable waters (e.g. seasonal waters or creeks) from the NWPA approval requirement. The amendments also authorized the Minister of Transport or the federal Cabinet to add to the list of exempted works or waterways, without subjecting these powers to any limited set of objective criteria.12 While bridges, booms, dams and causeways had always been deemed to interfere substantially with navigation under the pre-2009 NWPA, the amendments allowed the Minister to unilaterally and pre-emptively decide that such projects would not substantially interfere with navigation, resulting in the avoidance of previously mandatory public consultation requirements discussed below.

By allowing certain projects to proceed without an NWPA approval, the federal government achieved its broader deregulatory objective of reducing the number of projects subject to a federal environmental assessment. This rollback of federal environmental assessment was completed with amendments to CEAA in the 2012 omnibus budget bill, pursuant to which all NWPA approvals ceased to automatically trigger a federal environmental assessment.

In addition, the amended NWPA no longer requires public notice and comment opportunities for any projects that would not substantially interfere with navigation,13 and Ministerial powers can be exercised without public consultation or Parliamentary review.14 So while modernizing and streamlining the NWPA regulatory regime was top-of-mind, it is clear that this objective was taken to such an extreme that even the most basic of transparency mechanisms was sacrificed.

On the positive side, a number of inspection and enforcement powers were added to the NWPA in 2009, and penalties for offences were increased to a maximum of six months imprisonment or a $50,000 fine. In addition, the Minister was given the power to obtain an injunction to prevent an offence.15

11 NWPA, s. 5.1.

12 NWPA, ss. 12(1)(e), 13(1)(a).

13 NWPA, s. 9(3), (4), (5).

14 NWPA, s. 13(2): Ministerial orders exempting works and waterways from the approval process are not statutory instruments governed by the Statutory Instruments Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. S-22. Sections 19 and 19.1 of the Statutory Instruments Act require that all statutory instruments be referred to committees of either or both Houses of Parliament for review and scrutiny.

15 NWPA, s. 38.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

But enforcement improvements notwithstanding, the overall NWPA reform thrust in 2009 was one of deregulation and exclusion of public consultation and debate. As the section below articulates, the newly proposed changes to the NWPA further erode Canada’s legislative protections of both navigable waters and navigation rights.

What do the proposed changes in Bill C-45 mean?

The NWPA’s effectiveness as an environmental and navigational protection tool was significantly impaired by the 2009 amendments and the 2012 omnibus budget bill (Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act). The latter rolled back and re-wrote the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act such that approvals issued under the NWPA no longer trigger a federal environmental assessment.

The amendments proposed in Bill C-45 continue this dangerous deregulation of Canada’s waterways. While the overall impact of the proposed Navigation Protection Act on navigation and the environment is negative, it must be acknowledged that some of the proposed amendments might benefit navigation and the environment. The most significant amendments are discussed below.

1) Drastic Reduction in Number of Protected Waterways

The NPA would maintain the tiered classification system introduced in 2009, which grant the Minister authority to exempt specific works and waterways from the NPA approval process.16 The exercise of this power is not subject to Parliamentary oversight.17

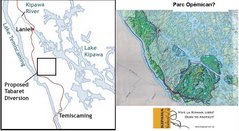

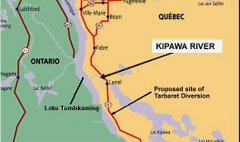

But by far the most significant change, if enacted, is that the NPA will not protect the vast majority of Canada’s waterways from development that interferes with navigation. Rather, the government will leave it to citizens to use the common law to achieve this protection. The NPA will only protect navigation on waters listed in a schedule to the Act.18 The proposed schedule19 includes 3 oceans, 97 lakes, and portions of 62 rivers. By comparison, Canada is estimated to contain at least 32,000 lakes and more than 2.25 million rivers: The NPA would exclude 99.7 per cent of Canada’s lakes and more than 99.9 per cent of Canada’s rivers from federal oversight. Notably absent from the proposed schedule are significant rivers in British Columbia, such as the Kitimat and Upper Fraser Rivers, which lie along the path of the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline. Notably included are popular cottage-country lakes such as those in Muskoka, where wealthy powerboat owners will continue to enjoy unfettered navigation protections.

Practically speaking, this means that the vast majority of non-listed Canadian navigable waters will be left unprotected in the following ways:

16 See sections 10 and 28(2)(a) and (b) of the proposed NPA.

17 Section 28(5) of the proposed NPA.

18 Section 3 of the proposed NPA prohibits the construction, operation, etc. of works only in navigable waters listed in the schedule, except in accordance with the NPA.

19 Transport Canada, Navigation Protection Act: Proposed List of Scheduled Waters, online: Transport Canada

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

Proponents will not have to notify the government that they are building a work that interferes with navigation;

Proponents will not need the Minister of Transport’s approval before building a work that interferes with navigation; and

The Minister of Transport will have no legislative authority under the NPA to remove obstructions or require that owners of such obstructions do so themselves, with one exception.20 Beyond infringing the right of navigation, this may have significant environmental consequences, as sunken vessels and other obstructions may indefinitely release harmful substances into waterways without a removal requirement.

The NPA would allow the owner of a work to opt into the regulatory process, if the Minister deems it justified in the circumstances.21 This means that where a proponent wants to build a work in a non-listed navigable water, the proponent may ask the Minister to be regulated under the NPA. Although the government claims that proponents may wish to opt in to avoid the uncertainty of the common law protections of navigation rights (see below), this provision inappropriately places the decision of applying the regulatory regime in the hands of the proponent. It also reduces transparency and accountability in decision-making.

The NPA would also allow the federal Cabinet (Governor-in-Council) to enact regulations adding navigable waters to the schedule list, but only if such additions are: i) in the national or regional economic interest; ii) in the public interest; or, iii) requested by a local authority.22 However, there is no requirement that Cabinet add to the schedule and none of these criteria explicitly incorporates sustainability or environmental protection considerations.

The deregulation proposed by the NPA could have significant impacts for aboriginal rights. Although the Crown has a duty to consult and, where appropriate, accommodate aboriginal peoples where the Crown is contemplating conduct that could adversely impact aboriginal rights, no such duty lies on private entities. Since the NPA would remove all government “conduct” from decision-making for non-listed navigable waters, it is possible that unregulated projects interfering with navigation could also negatively impact aboriginal rights without any consultation or accommodation.

2) Lack of Accountability, Transparency and Public Participation in Decision-making

The drastic reduction in the number of navigable waters that would be protected by the NPA will lead to decreased accountability, transparency and public

20 The obstruction provisions in Part II of the proposed NPA are limited to listed navigable waters, with one exception. Under section 16(2) of the proposed NPA, the Minister’s power to order an obstruction removed or destroyed applies where the obstruction is on federal property.

21 Section 4 of the proposed NPA.

22 Section 29 of the proposed NPA.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

participation in decision-making involving deregulated waterways. However, the NPA would also limit accountability, transparency, and public participation in decision-making involving those few remaining regulated navigable waters.

Consistent with the 2009 NWPA amendments, the NPA would remove Ministerial orders (including orders to exempt classes of works and waterways) from normal Parliamentary oversight. While notice of the orders would have to be published in the Canada Gazette within 23 days, the orders are shielded from the usual pre-publication public comment period and from Parliamentary review. 23

Significantly, the NPA would remove all automatic public participation opportunities. Whereas public notice and comment periods remain mandatory under the NWPA for projects which will substantially interfere with navigation on listed waterways, the NPA would make all public notice and comment requirements discretionary.24 This means that the Minister could choose to fast-track a project that substantially interferes with navigation without providing for public comment or any notice.

The NPA would also allow the Minister to sign agreements to delegate any responsibility, power, or duty under the Act.25 Such agreements could be reached with any person or organization and it is fair to presume that provincial and municipal governments are the target of this delegation provision. This raises questions about the capacity, financial and otherwise, of these levels of government to adequately implement navigation regulation. It also raises questions about what oversight mechanisms the federal government might employ to ensure any such delegated administration of navigation regulations is adequately implemented.

Some proposed amendments may have positive effects on accountability and transparency in decision-making for the limited set of listed regulated waterways. For example, the NPA would include a non-exhaustive list of criteria for the Minister to consider in determining whether a work would substantially interfere with navigation. The listed factors include the characteristics of the navigable water in question, the safety of navigation, the current or anticipated navigation in that water, the impact of the work on navigation in that water, and the cumulative impact of the work on navigation in that water.26 Although providing clarity, this list identifies obvious factors that are likely considered in any event, so its benefit is minimal. Unfortunately, with this clarity comes certainty that these factors do not include environmental concerns as a required consideration.

Furthermore, if public comments are solicited by the Minister, they will be used to inform the substantial interference decision. To the degree such comments

23 See section 28(5) of the proposed NPA.

24 Sections 5(6) and (7) of the proposed NPA.

25 Section 27 of the proposed NPA.

26 Section 5(4) of the proposed NPA.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

are sought, this will enhance public participation by engaging the public at an earlier stage in the decision-making process. The current public participation requirements under the NWPA are only triggered after the Minister makes the substantial interference decision, and are presumably used to inform terms and conditions imposed on an approval.

In conclusion, while Bill C-45 does offer marginal improvements, the overall effect of the new NPA regime would be to decrease accountability, transparency, and public participation in the protection of Canada’s navigable waters.

3) Retention of Dumping Prohibitions and Closing of Loopholes

The dumping of foreign materials, objects and debris into navigable waters may have serious negative impacts on both navigation and navigable waters. The dumping provisions contained in the existing NWPA are retained in the NPA with slight modifications to update the language.27 Significantly, these prohibitions apply to all navigable waters, and are not limited to those waters listed in the schedule to the NPA.

In addition, the Bill C-45 amendments would prohibit the dewatering of any navigable water.28 This is a positive reform, as it has become clear that unscrupulous mining companies have sought to avoid regulatory restrictions under the NWPA dumping prohibitions by dewatering streams prior to depositing waste in them. This amendment is intended to close that loophole and represents an important strengthening of the dumping prohibitions.

While strengthening the dumping prohibitions on paper, the impact of these amendments may be limited by the government’s dedication of resources to enforce the prohibitions. The government’s stated purpose in amending the NWPA is to “focus Transport Canada’s resources on the country’s most significant waterways.”29 Given this position and broader fiscal constraints, it is highly questionable whether Transport Canada will devote sufficient resources, if it devotes any at all, to enforce dumping prohibitions for navigable waters not listed in the schedule to the NPA. As a result, this beneficial amendment may amount to nothing more than a paper tiger.

4) Enhancement of Enforcement Powers

Although broad enforcement powers were included in the NWPA for the first time in 2009, the proposed NPA would expand upon these powers.

As regards enforcement, the NPA would create a new administrative monetary penalty (AMP) regime to complement the existing and separate offences regime (under which contraventions could result in a maximum of six months imprisonment or a $50,000 fine, or both).

27 Sections 21 and 22 of the proposed NPA.

28 Section 23 of the proposed NPA.

29 Transport Canada, “Speaking notes for the Honourable Denis Lebel, Minister of Transport, Infrastructure and Communities for the announcement of proposed amendments to the Navigable Waters Protection Act,” online: Transport Canada

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

Under the AMP regime, persons designated by the Minister could issue a notice of violation to any person contravening designated provisions of the NPA.30 Individual and corporate violations would be subject to maximum fines of $5,000 and $40,000 respectively.31 Proof of contested violations would be on a balance of probabilities32 and subject to a due diligence defence,33 with a right of appeal regarding the commission of the violation and the penalty amount to the Transportation Appeal Tribunal of Canada.34

The Minister’s power to obtain an injunction, introduced in 2009, would be preserved, and would apply to the prevention of violations as well offences.35

The incorporation of an AMP regime would provide a mechanism for the government to more easily and inexpensively enforce contraventions of the NPA. Whereas enforcing the offences provisions of the NPA would require the government to prove the offence beyond a reasonable doubt, the administrative monetary penalty regime provides for a lower standard of proof. The AMP regime also provides for simplified procedures and avoids the necessity of going to court.

The NPA would increase the number and types of offences punishable under the Act. For example, the NPA would impose a duty upon owners of works in listed waters to take corrective measures where the work causes or threatens to cause serious and imminent danger to navigation.36 Under this duty, all reasonable measures consistent with public safety and the safety of navigation must be undertaken as soon as feasible; measures may include steps to counteract, mitigate, or remedy adverse effects that actually or might reasonably result from the danger. An owner’s failure to discharge this duty would be an offence under the NPA.37

Finally, the NPA would explicitly recognize the liability of directors of corporations under both the administrative monetary penalty and offences regimes.38 This means that, if a corporation commits a violation or offence under the NPA, any officer or director of that corporation can be held personally liable for the violation or offence. In other words, if a corporation has no assets or goes bankrupt, the government can collect the fine from a director or officer of that corporation. In a similar vein, the NPA would impose a positive duty on directors and officers of corporations to take all reasonable care to ensure that the corporation complied with the NPA.39 Although this provision establishes a

30 Section 39.11 of the proposed NPA.

31 Section 39.1(3) of the proposed NPA.

32 Section 39.18 of the proposed NPA.

33 Section 39.17(1) of the proposed NPA.

34 Sections 39.13(1) and (2) of the proposed NPA.

35 Section 38(1) of the proposed NPA.

36 Section 12(2) of the proposed NPA.

37 Section 40(1)(e) of the proposed NPA.

38 For violations: section 39.19 of the proposed NPA. For offences: section 40(4) of the proposed NPA.

39 Section 40(5) of the proposed NPA.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

potential due diligence defence for corporate directors, it also makes clear the responsibility of those directors to actively ensure compliance with the NPA. This is a positive new development.

5) Pipelines, Power Lines and National Marine Conservation Areas

Bill C-45 also contains a number of proposed coordinating amendments relating to the NWPA. While these provisions mainly serve to change the name of the NWPA to NPA in other statutes, and do not introduce new changes, several of the provisions have environmental implications that are worthy of mention.

First, certain regulations made under the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act would retain their supremacy over regulations made under the NPA.40 This would apply to regulations pertaining to fisheries management, restricting or prohibiting marine navigation in marine conservation areas. Under the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act, these regulations must be made only with the joint approval of the Minister responsible for Parks Canada and the Minister of Transport. This means that the Minister of Transport cannot unilaterally exempt navigable waters from the NPA where those waters are located in a marine conservation area. This is a positive development.

Additional coordinating provisions confirm that pipelines and power lines are not works for the purposes of the NPA.41 In other words, the NPA doesn’t apply to large pipelines and power lines. NPA does apply to small pipelines that are classified as minor works; these are exempted from the approval process. These amendments are not new; they were amended pursuant to the Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act.42

As a result, the National Energy Board Act and Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act already provide that the National Energy Board (NEB) has jurisdiction over the navigational impacts of interprovincial/international and offshore oil and gas pipelines and power lines. Pursuant to sections 58.3 and 110(2) of the NEB Act, as amended by Bill C-38, the NEB "shall take into account the effects that its decision might have on navigation, including safety of navigation" when making decisions about such projects.43 However, these processes are not environmental assessments, and the degree to which the NEB is competent to assess the navigation impacts of pipelines is open to serious debate.

Due to the rollbacks of federal environmental assessment law with the enactment of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, it may be that this transfer of jurisdiction to the NEB enhances protection of navigable waters in some limited circumstances. While projects overseen by the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency may not be subjected to any environmental

40 See clause 342 of Bill C-45.

41 See clauses 349(2), (5) and (9) of Bill C-45.

42 S.C. 2012, c. 19, ss. 87, 91.

43 Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act, S.C. 2012, c. 19, ss. 87, 91.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

assessment, pipelines and power lines regulated by the NEB are subject to mandatory environmental assessments, pursuant to CEAA 2012.44

6) Reliance on the Common Law to Protect Navigation: An Inadequate Safety Net

The federal government has clearly stated that, to the extent the NPA will not protect navigation on non-listed navigable waters (ie. the majority of Canadian waterways), the common law applicable to navigation rights will still apply.45 The federal government appears to take the position that the common law actually provides stronger protection for navigation by stating that, at common law, the public right of navigation is prioritized over other interests.46 It is clear that, at common law, the public right of navigation is paramount to all other rights in navigable waters, as long as the right is exercised in a reasonable manner with due care not to harm others.47

This prioritization at common law contrasts with the NWPA’s dual mandate of “balancing the need to allow critical infrastructure to be built” with the right of navigation.48 But complicating this dual mandate is the interrelationship between navigation and its corollary aquatic environment, given that the protection of the former has historically promoted the health of the latter. Certainly, the maintenance of ecologically sustainable flow rates is inextricably linked to the maintenance of navigational flow requirements. In light of this relationship, it is reasonable to anticipate that Canadian courts will be called upon to determine whether, and to what degree, the common law right of navigation extends to protecting the aquatic environment.

At common law, obstructions that significantly interfere with navigation constitute a public nuisance. Generally, only the government is entitled to prosecute public nuisance offences, but private citizens may do so where they have suffered special damages above and beyond those suffered by the general public. Thus, for example, a canoe/kayak tour operation business harmed economically because a dam restricts guided river tours may bring an action to sue the owner of the dam for public nuisance. To be sure, this cause of action may still be available even where the dam is authorized under the NWPA, although the law on this question is unsettled.49 The government’s position articulated above does little more than clarify the common law reality that citizens may, in appropriate factual circumstances, sue owners of works that interfere with navigation for public nuisance.

44 The NEB will only have to conduct an environmental assessment for interprovincial/international or offshore pipelines and powerlines that are over 75 km in length and occur on a new right of way: Regulations Designating Physical Activities, SOR/2012-147, Schedule, ss. 34, 38.

45 http://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/mediaroom/backgrounders-npa-common-law-right-naviagtion-6907.htm

46 Transport Canada, Navigation Protection Act: Common Law and the Right of Navigation, online: Transport Canada:

47 Wood v. Esson, [1884] 9 S.C.R. 239.

48 http://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/mediaroom/backgrounders-npa-protection-waterways-6913.htm

49 Gerard V La Forest, Water Law in Canada – The Atlantic Provinces (Ottawa: Information Canada, 1973) [“Water Law in Canada”] at 251-252.

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

The lack of federal oversight for projects in non-listed navigable waters would make it extraordinarily difficult to enforce the public right of navigation on a consistent basis. Reliance on the common law to protect the majority of Canada’s waterways is problematic in several ways:

The government holds Canada’s resources in trust for Canadian citizens; as such it has a responsibility to ensure that public resources, including navigable waters, are not disrupted, depleted, or destroyed for present and future generations. By deferring to the common law as applied by Canadian courts to protect the majority of Canada’s navigable waterways, the government is shirking its responsibility to protect them and the public rights they underpin.

Reliance on the common law shifts the burden of protecting Canada’s waterways onto private citizens, public interest groups and businesses (ie. outdoor adventure companies) with a vested interest in preserving navigable waters as a public and economic resource. Most citizens and groups do not have the time or resources to pursue lawsuits, and this problem is often compounded by the inequality of resources as between those impacting navigation and those protecting it. Furthermore, it is inappropriate to require a private citizen to bear the costs and uncertainties associated with litigation in order to enforce a public right. In effect, this is the ultimate in “privatization” of Canada’s navigation regulatory regime. Paradoxically, the deregulation of Canada’s navigable waterways may result in increased uncertainty for project proponents in the face of sporadic, costly and time-consuming litigation based on common law protections of navigation rights.

The inclusion of the opt-in provision in section 4 of the NPA, which allows anyone building a work on a non-listed water to ask to be re-regulated, clearly indicates that the government anticipates that significant uncertainty will be generated by the litigation that will result from renewed reliance on the common law.

To the extent that citizens or public interest groups can finance lawsuits, the NPA amendments would make it nearly impossible to identify works that substantially interfere with navigation, by removing public notice requirements for all but a select few projects. Without knowing what works are being planned, it will be next to impossible to ensure that they do not interfere with the right of navigation.

The government has suggested that the common law will uphold a citizen’s right to remove a navigational obstruction.50 While courts in the past have recognized the rights of navigators to remove obstacles to navigation, this right only arises when the navigator has suffered special

50 Transport Canada, Navigation Protection Act: Common Law and the Right of Navigation, online: Transport Canada:

Published by Ecojustice, October 2012

For more information, please visit: ecojustice.ca

damages from the interference with navigation, and must be exercised reasonably and with due care to avoid causing harm to others.51 Aside from encouraging vigilantism, this approach to the common law places an inordinate amount of risk on private citizens, effectively encouraging them to risk being sued in order to uphold their right of navigation.

Reliance on the common law as a safety net beneath a less comprehensive NPA embraces a strongly reactive, rather than proactive and precautionary, approach to regulating navigable waters. Courts will generally only compensate harm after it has occurred, and given the lack of public notice requirements for projects related to non-listed waters, obtaining an injunction would be extremely difficult. As a result, reliance on the common law inherently encourages the infringement of the public right of navigation, with a remote possibility of remedying harms after they have occurred.

Conclusion

Although a handful of proposed amendments to the NWPA in Bill C-45 may enhance protection of navigation and navigable waters, the overall deregulatory impact will be to weaken Canadians’ public right of navigation. In essence, the federal government is doing its utmost to “get out of the business” of protecting navigable waterways across the country, except for three oceans, 97 lakes, and portions of 62 rivers. The majority of Canada’s waterways will not be subject to statutory navigation protections, leaving citizens clinging to the leaky lifeboat of common law in the fast-moving currents of economic growth.

51 Zwicker

No comments:

Post a Comment